Jonathan Green – The Freedom Ship of Robert Smalls

City Gallery, in partnership with the MOJA Arts Festival and the Charleston 350 Commemoration Commission, presents The Freedom Ship of Robert Smalls, on view from October 29, 2020. This exhibition presents large format reproductions of artist Jonathan Green’s illustrations for Louise Meriweather’s childrens’ book, The Freedom Ship of Robert Smalls. Originally published in 1971, the new edition of the book, reprinted in 2018 by USC Press’s Young Palmetto Books, includes fifteen vivid and colorful illustrations by Green detailing Robert Smalls’ dramatic escape from slavery in 1862.

Jonathan Green’s vibrant and colorful illustrations are presented at City Gallery with highlights from the book, alongside historical information about the life and legacy of Robert Smalls. The exhibition offers an in-person experience that extends and enhances the virtual programs of the MOJA Arts Festival and Charleston 350 Commemoration, set in close physical proximity to the sites associated with this historic event. Additional information about Smalls, including links to educational and archival resources online, are available on the City Gallery’s website, HERE. This project has been graciously supported by Dominion Energy, with additional assistance from the Friends of MOJA.

Due to the ongoing situation related to COVID-19 in South Carolina, City Gallery will re-open with adjusted hours and safety precautions starting Thursday, October 29, 2020. Guests are requested to reserve in advance online or by phone for free, timed admission, with exhibition viewing offered Thursdays through Sundays from noon until 5pm (last daily reservation at 4:40pm). Reservations will initially be available through Sunday, November 22. Face masks will be required of all guests and staff, and staff will monitor circulation through the exhibition to ensure safe social distancing throughout the facility and adherence to all other CDC protocols related to COVID-19. Sanitizer stations will be provided in the gallery, and staff will use enhanced cleaning protocols for all City Gallery spaces throughout the day.

Reservations are available below; guests may also reserve by phoning the gallery at (843) 958-6484 during regular business hours.

All underlined facts can be found chronologically on the Robert Smalls Timeline

To order your book copy of The Freedom Ship of Robert Smalls, follow the link below:

https://www.sc.edu/uscpress/books/2018/7855.html

Birth – April 1839

Robert Smalls was born on April 5, 1839 to Lydia Polite, a woman enslaved by Henry McKee, who was most likely Smalls’ father.

She gave birth to him in a cabin behind McKee’s house, at 511 Prince Street in Beaufort, South Carolina.

Charleston – 1851-1860

When he was 12, at the request of his mother, Smalls was sent to Charleston in 1851 to be hired out as a laborer for one dollar a week, with the rest of the wage being paid to his master.

The youth first worked in a hotel, then became a lamplighter on Charleston’s streets. In his teen years, his love of the sea led him to find work on Charleston’s docks and wharves. Smalls worked as a longshoreman, a rigger, a sail maker, and eventually worked his way up to become a wheelman, more or less a helmsman, though slaves were not permitted that title. As a result, he was very knowledgeable about Charleston harbor.

Family Man – 1856

With his first wife Hannah Jones Smalls, whom he married on December 24, 1856, Robert Smalls had three children: Elizabeth Lydia (1858–1959; m. Samuel Jones Bampfield, nine living children); Robert Jr. (1861–1863), who died at the age of two; and Sarah Voorhies (1863–1920)

Robert and his wife Hannah pictured later in their lives

Courtesy of Michael Boulware Moore

Escape from Slavery – 1861-1862

In the fall of 1861, Smalls was assigned to steer The CSS Planter, a lightly armed Confederate military transport under the command of Charleston’s District Commander Brigadier General Roswell S. Ripley. The Planter‘s duties were to deliver dispatches, troops and supplies, to survey waterways, and to lay mines.

From Charleston harbor, Smalls and The Planter‘s crew could see the line of federal blockade ships in the outer harbor, seven miles away. Smalls appeared content and had the confidence of The Planter‘s crew and owners, and at some time in April 1862, Smalls began to plan an escape.

On the evening of May 12 1862, The Planter was docked as usual at the wharf below General Ripley’s headquarters. Its three white officers disembarked to spend the night ashore, leaving Smalls and the crew on board, “as was their custom.”

However, before the officers departed, Smalls asked Captain Relyea if the crews’ families could visit, which was occasionally allowed, and he approved on condition that they depart before curfew. When the families arrived, the men revealed the plan to them.

This was the first the women and children had heard of it, although Smalls recently had told [his wife] Hannah. She had known that Smalls longed to escape but hadn’t realized that he was formulating a plan and intended to execute it. She was taken aback but quickly regained her composure and told him, “It is a risk, dear, but you and I, and our little ones must be free. I will go, for where you die, I will die.”

The other women were less steadfast. They cried and screamed when they learned what they had stumbled into, and the men struggled to quiet them. Later, once the shock had worn off, those women admitted that they were glad for a chance at freedom.

At some point, three crew members pretended to escort family members back home but circled around and hid aboard another steamer docked at the North Atlantic wharf. At about 3 a.m. May 13, 1862 Smalls and seven of the eight slave crewmen made their previously planned escape to the Union blockade ships. Smalls put on the captain’s uniform and wore a straw hat similar to the captain’s. He sailed The Planter past what was then called Southern Wharf and stopped at another wharf to pick up his wife and children and the families of other crewmen.

Smalls guided the ship past the five Confederate harbor forts without incident, as he gave the correct signals at checkpoints. The Planter sailed past Fort Sumter at about 4:30 a.m.

As the nearly-free slaves approached Fort Sumter, their apprehension began to grow. It was the most heavily armed of the forts and tended to be manned by the most suspicious soldiers. One of the men aboard later said, “When we drew near the fort every man but Robert Smalls felt his knees giving way and the women began crying and praying again.…As The Planter approached the fort, several men urged Smalls to give it a wide berth. Smalls refused, saying that such behavior would almost certainly arouse suspicion. He steered the ship along its normal path, slowly, as though he were merely enjoying the early morning air and in no particular hurry. When Fort Sumter flashed the challenge signal, Smalls again gave the correct hand signs. There was a long pause. The fort didn’t immediately respond, and Smalls now expected cannon fire to shred The Planter at any moment. Finally, the fort signaled that all was well, and Smalls sailed his ship out of the harbor.

The alarm was only raised after the ship was beyond gun range. Rather than turn east towards Morris Island, Smalls had headed straight for the Union Navy fleet, replacing the rebel flags with a white bed sheet which was brought by his wife. The Planter had been seen by the USS Onward, which was about to fire until a crewman spotted the white flag.

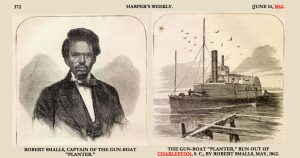

Newspaper pictures of Robert Smalls and gun boat The Planter from Harper’s Weekly: June 14, 1862

Eye witness account:

Just as No. 3 port gun was being elevated, someone cried out, “I see something that looks like a white flag”; and true enough there was something flying on the steamer that would have been white by application of soap and water. As she neared us, we looked in vain for the face of a white man. When they discovered that we would not fire on them, there was a rush of contrabands out on her deck, some dancing, some singing, whistling, jumping; and others stood looking towards Fort Sumter, and muttering all sorts of maledictions against it, and “de heart of de Souf,” generally. As the steamer came near, and under the stern of the Onward, one of the Colored men stepped forward, and taking off his hat, shouted, “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!” That man was Robert Smalls.

The Onward‘s captain, John Frederick Nickels, boarded The Planter, and Smalls asked for a United States flag to display. He surrendered The Planter and its cargo to the US Navy, Smalls’ escape plan had succeeded.

Smalls gave detailed information about Charleston’s defenses to Flag Officer Du Pont, commander of the blockading fleet. Federal officers were surprised to learn from Smalls that contrary to their calculations, only a few thousand troops remained to protect the area, the rest having been sent to Tennessee and Virginia.

This intelligence allowed Union forces to capture Coles Island and its string of batteries without a fight on May 20, 1862 a week after Smalls’ escape.

Du Pont was impressed, and wrote the following to the Navy secretary in Washington: “Robert, the intelligent slave and pilot of the boat, who performed this bold feat so skillfully, informed me of [the capture of the Sumter gun], presuming it would be a matter of interest.” He “is superior to any who have come into our lines — intelligent as many of them have been.”

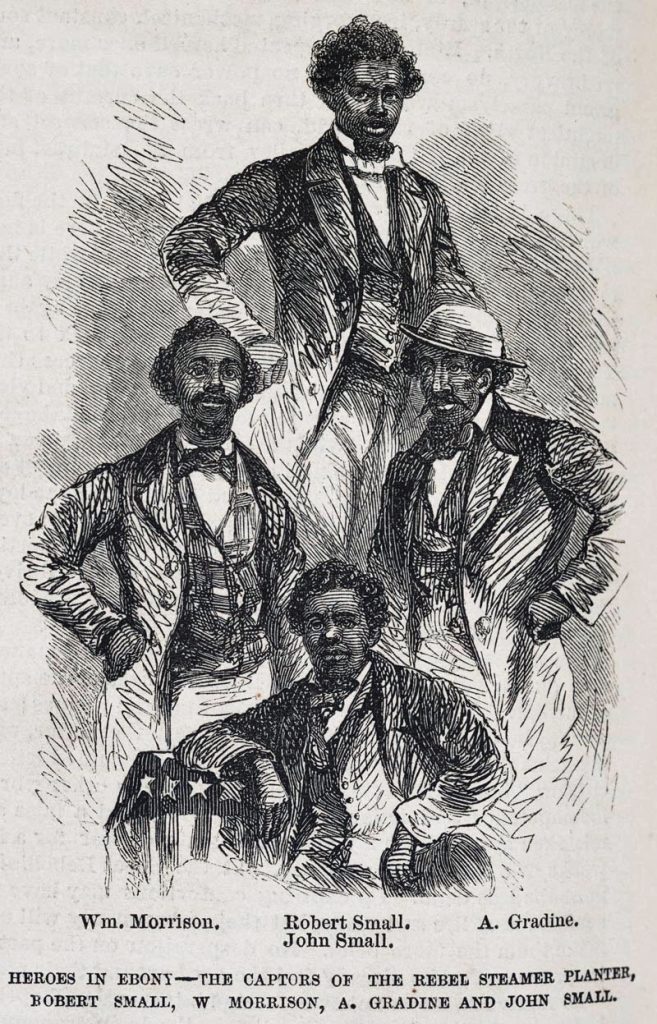

“Heroes in Ebony”

1860’s Drawing of the 4 mutineers of the Confederate gun-boat The Planter

Navy Pilot – Summer 1862

Smalls, having just turned 23, quickly became known in the North as a hero for his daring exploit. Newspapers and magazines reported his actions. The U.S. Congress passed a bill awarding Smalls and his crewmen the prize money for The Planter (valuable not only for its guns but low draft in Charleston bay); Southern newspapers demanded harsh discipline for the Confederate officers whose joint shore leave had allowed the slaves to steal the boat.

Smalls’ share of the prize money came to US$1,500 (equivalent to $38,415 in 2019).

Immediately after the capture, Smalls was invited to travel to New York to help raise money for ex-slaves, but Admiral DuPont vetoed the proposal and Smalls began to serve the Union Navy, especially with his detailed knowledge of mines laid near Charleston. However, with the encouragement of Major General David Hunter, the Union commander at Port Royal, Smalls went to Washington, D.C. to persuade Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to permit black men to fight for the Union.

Although Lincoln had previously rescinded orders by Hunter and Generals Fremont and Sherman to mobilize black troops, Stanton soon signed an order permitting up to 5,000 African Americans to enlist in the Union forces at Port Royal. Those who did were organized as the 1st and 2nd South Carolina Regiments.

Smalls worked as a civilian with the Navy until March 1863, when he was transferred to the Army. By his own account, Smalls was present at 17 major battles and engagements in the Civil War.

Smalls was made pilot of the Crusader under Captain Alexander Rhind.

Navy Captain – 1863

He was later made pilot of the ironclad USS Keokuk, again under captain Rhind, and took part in the attack on Fort Sumter on April 7, 1863, which was a preamble to the Second Battle of Fort Sumter later that fall.

On December 1, 1863, Smalls was piloting The Planter under Captain James Nickerson on Folly Island Creek when Confederate batteries at Secessionville opened. Nickerson fled the pilot house for the coal-bunker. Smalls refused to surrender, fearing that the black crewmen would not be treated as prisoners of war and might be summarily killed. Smalls entered the pilothouse and took command of the boat and piloted it to safety. For this, he was reportedly promoted by Gillmore to the rank of captain and made acting captain of The Planter.

1864

In May 1864, he was voted an unofficial delegate to the Republican National Convention in Baltimore. Later that spring, Smalls piloted The Planter to Philadelphia for repairs.

In Philadelphia, he supported what was known as the Port Royal Experiment, an effort to raise money to support the education and development of ex-slaves. At the outset of the Civil War, Smalls could not read or write, but he achieved literacy in Philadelphia.

December 1864 – Summer 1865

In December 1864, Smalls, and The Planter, moved to support William T. Sherman’s army in Savannah, Georgia, at the destination point of his March to the Sea.

Smalls returned with The Planter to Charleston harbor in April 1865 for the ceremonial raising of the American flag again at Fort Sumter.

Smalls was honorably discharged on June 11, 1865.

He continued to pilot The Planter, serving a humanitarian mission of taking food and supplies to freedmen who lost their homes and livelihoods during the war until September 30th, 1865.

After The War – 1865

Immediately following the war, Smalls returned to his native Beaufort, where he purchased his former master’s house at 511 Prince St, which Union tax authorities had seized in 1863 for refusal to pay taxes.

The Robert Smalls House – 511 Prince St. Beaufort, SC

His mother, Lydia, lived with him for the remainder of her life. He allowed his former master’s wife, the elderly Jane Bond McKee, to move into her former home prior to her death.

Smalls spent nine months learning to read and write. He purchased a two-story Beaumont building to use as a school for African-American children.

Business Life – 1866 – 1872

In 1866 Smalls went into business in Beaufort with Richard Howell Gleaves, a businessman from Philadelphia. They opened a store together to serve the needs of freedmen. Smalls also hired a teacher to help him study.

Smalls invested significantly in the economic development of the Charleston-Beaufort region. In 1870, in anticipation of a Reconstruction-based prosperity, Smalls, with fellow representatives Joseph Rainey, Alonzo Ransier and others, formed the Enterprise Railroad, an 18-mile horse-drawn railway line that carried cargo and passengers between the Charleston wharves and inland depots. Except for one director, Timothy Hurley, the railroad’s board of directors was entirely African American.

Later serving as SC Representative, Richard H. Cain was the railway’s first president.

Smalls owned and helped publish a black-owned newspaper, the Beaufort Southern Standard starting in 1872.

State Politics – 1868 -1874

Smalls was a loyal Republican which, at the time, dominated the Northern States and passed laws that granted protections for African Americans, whereas the Democrats, who dominated the South, opposed these measures.

After the Civil War, Republicans passed laws that granted protections for African Americans and advanced social justice; again, Democrats, at the time, largely opposed these expansions of power.

Smalls was a delegate at the 1868 South Carolina Constitutional Convention where he was a part of the effort to make free, compulsory schooling available to all South Carolina children.

In 1868, Smalls was elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives. He was very effective, and introduced the Homestead Act and introduced and worked to pass the Civil Rights bill.

In 1870, Jonathan Jasper Wright was elected judge of the South Carolina Supreme Court and Smalls was elected to fill his unexpired time in the Senate.

He continued in the Senate, winning the 1872 election against W. J. Whipper.

He was a delegate to the National Republican Conventions in 1872 in Philadelphia, which nominated Grant for president; in 1876 in Cincinnati, which nominated Hayes; and in 1884 in Chicago, which nominated Blaine—and then continuously to all conventions until 1896.

He was also elected vice-president of the South Carolina Republican Party at their 1872 state convention.

In 1873, he was appointed lieutenant-colonel of the Third Regiment, South Carolina State Militia. He was later promoted to brigadier-general of the Second Brigade, South Carolina Militia, and the major-general of the Second Division, South Carolina State Militia.

National Politics – 1874 -1887

In 1874, Smalls was elected to the United States House of Representatives, where he served two terms from 1875 to 1879.

From 1882 to 1883, he represented South Carolina’s 5th congressional district in the House.

The state legislature gerrymandered to change the district boundaries, including Beaufort and other heavily black, coastal areas in South Carolina’s 7th congressional district, giving the others substantial white majorities.

Smalls was elected from the 7th district and served from 1884 to 1887. He was a member of the 44th, 45th, 47th, 48th, and 49th U.S. Congresses.

He was the second-longest serving African-American member of Congress (behind his contemporary Joseph Rainey) until the mid-20th century.

A scandal took a political toll on Smalls during his run for Congressman, and he was defeated by Democrat George D. Tillman in 1878, and again, narrowly, in 1880. He successfully contested the 1880 result and regained the seat in 1882. In 1884, he was elected to fill a seat in a different district.

During this period in Congress he supported racial integration legislation, supported a pension for the widow of his former Major General, David Hunter, and advised South Carolina blacks to refrain from emigrating to the North and Midwest or to Liberia.

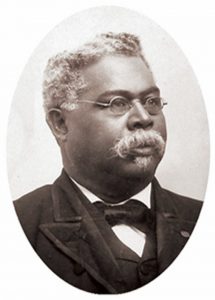

Later Life Facts –1890 – 1912

In 1890, he was appointed by President Benjamin Harrison as Collector of the Port of Beaufort, which he held until 1913 except during Democrat Grover Cleveland’s second term.

He was a delegate to the 1895 South Carolina constitutional convention.

In the late 1890s, he began to suffer from diabetes. He turned down an offer of a colonelcy of a black regiment in the Spanish-American War and to the post of minister to Liberia.

In words that became famous, he described his party as “the party of Lincoln…which unshackled the necks of four million human beings.” He wrote this line on September 12, 1912, in a letter expressing his anxiety over the looming presidential election.

In 1913, in one of his final actions as community leader, he played an important role in stopping a lynch mob from killing two black suspects in the murder of a white man. He pressured the mayor, saying that blacks he had sent throughout the city would burn the town down if the mob was not stopped. The mayor and sheriff stopped the mob.

Death – 1915

Robert Smalls died of malaria and diabetes on February 13, 1915 at the age of 75. He was buried in his family’s plot in the churchyard of the Tabernacle Baptist Church in downtown Beaufort.

The monument to Smalls in the Tabernacle Baptist Churchyard is inscribed with a statement he made to the South Carolina legislature in 1895:

“My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere.

All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

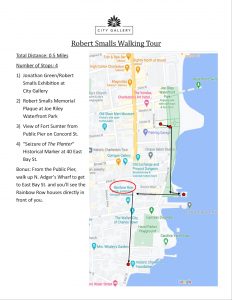

ROBERT SMALLS DOWNTOWN CHARLESTON WALKING TOUR

After coming to see the latest Jonathan Green/Robert Smalls Exhibition at City Gallery, take a walk in the steps of history with our Robert Smalls Walking Tour!!

At only 0.5 miles long, and with only 4 listed stops, it will take most people less than 15 minutes to complete the entire tour.

Stop #1: Current Exhibition being displayed at City Gallery

Stop #2: Robert Smalls Memorial Plaque in Joe Riley Jr. Waterfront Park

Stop #3: Public Pier off Cordes St. Walk safely to the edge of the pier and see Fort Sumter less than a mile away!

Bonus! Walk from the public pier up N. Adger’s Wharf to get to E. Bay St. You’ll be met with the sight of the infamous Rainbow Row houses directly in front of you.

Stop #4: Walk towards the Battery along E. Bay St. and find the Historical Marker signifying “The Seizure of The Planter” just outside the Historical Charleston Society Building located at 40 E. Bay St.

Extra Facts

- The Robert Smalls House in Beaufort, South Carolina, has been designated a National Historic Landmark and sold for $1.5m in 2018.

- A monument and statue are dedicated to his memory where he is interred at Tabernacle Baptist Church in Beaufort.

- February 22nd, 1976 was declared “Robert Smalls Day” by South Carolina Governor James B. Edwards.

- Since 1989, a 15-mile stretch of US highway 170 (into Beaufort) was named after Robert Smalls.

- On May 13, 2002 (The 140th anniversary of the capture of The Planter) Robert Smalls was posthumously awarded the Palmetto Cross “for exceptionally outstanding service while serving in the South Carolina Militia between 1870 and 1877.”

- The Robert Smalls School in Cheraw, South Carolina, is named for him.

- The Robert Smalls International Academy (formerly the Robert Smalls Middle School) in Beaufort County, South Carolina, is named for him.

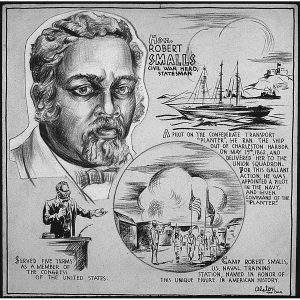

- During World War II, Camp Robert Smalls was established as a sub-facility of the Great Lakes Naval Training Center to train black sailors (the Navy was segregated in those years).

Newspaper drawing for the opening of Navy Camp Robert Smalls in 1942

- There is a proposal to create a statue of Robert Smalls to be installed at the South Carolina State House.

- Smalls was one of two blacks present at both the 1868 and 1895 South Carolina Constitutional Conventions

Works Cited:

All listed information can be found at these links:

The Freedom Ship of Robert Smalls by Louise Meriwether

NY Times – Robert Smalls’ Great Escape

Civil War Preservation Trust – Civil War Figures as Examples of Character and Leadership

All photos used can be found at these links: